Short and long

This is a draft of an excerpt from my forthcoming book about the Clay-Chalkville football program.

May 6 and May 12, 2025

My son had a kindergarten orientation the evening of May 6, 2025, so practice was a short one for me.

As had become my norm for the first two practices, I checked in at the coaches’ offices on the second floor of the fieldhouse. A sheet of paper taped to a wall, which I had not yet noticed, greeted me. It notified of team Bible studies on Fridays at seven o’clock in the morning in Coach Floyd’s office.

In the hallway, I listened as coaches recapped the Kentucky Derby, which Sovereignty won over the highly favored horse, Journalism. When I do watch the Kentucky Derby, which is rare, I pull for the underdog, but I wanted the favorite to win that day. A win for any type of Journalism would have been cool. Sovereignty pulled ahead during the final stretch in the Run for the Roses at a muddy Churchill Downs. It was announced two days later that Sovereignty would not compete in the Preakness Stakes, nullifying any chance at a Triple Crown. There was discussion among the Clay-Chalkville coaches about why this was the decision. Among the reasons were rest for the horse, potential injuries, and money.

As the coaches headed down the stairs to walk through the weight room and onto the field, Burdette, the wide receivers coach, said, “Some horses just aren’t built for the Triple Crown.”

As defensive coordinator Jake Helveston pushed a sled toward midfield, I asked if his defenders would have more juice in this practice than the previous day.

“If they have any, it’ll be more,” he joked.

From what I saw in my hour and a half on the field, both sides of the ball had more juice. In position drills, Floyd seemed to spend more time than usual with the defense. A sense of urgency was evident.

“Wake up!” I heard him holler. “Hurry up!”

During the portion of practice in which the first-team offense faces the first-team defense, quarterback Aaron Frye lobbed a three-yard fade to wide receiver Jacori Johnson for a touchdown. Johnson spiked the ball, and offensive teammates who were in on the play, and others from the sideline, rushed to celebrate.

In defensive drills, Helveston picked one of a handful of people – an injured player, other coaches – to throw the football to, and the entire defense, all eleven players, were required to run to that ball catcher and keep their feet moving. Only then did the drill, all about getting to the ball quickly, end. On one of the longest throws Helveston made, Floyd made the defense return to the receiver once more because at least one defender did not keep his feet moving until the end of the drill. A group of eleven must play as one.

***

I returned to Clay-Chalkville six days later for spring practice. I planned to stay the full two hours of practice and a little while afterward. Thunderstorms were all over Alabama that day and expected to affect the Clay area around the time practice was set to start. Of course. As I made the same drive up Deerfoot Parkway, the clouds were dark blue and a menacing gray. There was no sunlight. Coaches were checking weather apps on their phones when I arrived. I saw Helveston in the hall near the window that overlooks the football field. I had heard that a scrimmage three days prior went well for his side of the ball.

“We were due,” he said.

Floyd, an avid weather follower – I saw him recording videos of torrential rain before a game against Ramsay at historic Legion Field in 2024 – was sitting at his computer in his office. The book the team had read earlier in the spring, Legacy, sat atop a stack of four others. He was printing information for practice, perhaps the day’s script, and listening to music. I have long been accustomed to the playlists before football practices and games. Typically, the genres range from new rap to old rock and roll, with the occasional fast-paced country song mixed in. Floyd was listening to a song by Amy Winehouse, and I think he said something about singing it out loud in a Waffle House.

I gestured toward the book on his desk and asked what section stood out the most to him. He said the writings about “dual leadership” – transferring leading from coach to player, and then player to player – were the most meaningful. He remembered that Curtis Coleman, a legendary defensive line coach in Alabama high school football, would teach his starting front four to teach the players behind them on the depth chart.

“This whole book for me is how to create leaders,” Floyd said. “How do you create the environment? How do you teach them how to lead and when to lead?”

Players were more aware of who I was that day. Consistency was paying off for me. Most folks believe a journalist must be naturally extroverted to succeed. Not the case. I always enjoyed telling stories, but talking to people was often tough. Truthfully, that was what made journalism worth it for me. The challenge. It was a fear to face interviewing someone in their saddest moments, or ask a city councilor a tough question, or ask Nick Saban anything in front of other assembled writers. As soon as I stepped onto the field, where only five stray raindrops hit me, an offensive lineman asked me, by name, how I was doing. I had a long conversation with Joseph Del Toro, the team’s kicker. He told me that he previously attended Pinson Valley High School, a city over, where he played soccer but not football. He remembered sitting in the visitor stands in September 2023, when Pinson Valley played at Clay-Chalkville. The Cougars won, 41-0. He said he was only going to try to be a kicker for a football team if it was at Clay-Chalkville.

We talked about his mindset as a kicker, the loneliest position on a football team, why he chose to size his cleats down to size ten from ten-and-a-half, and how his team picked up his spirits when he missed kicks. He trotted onto the field not long after our conversation. On his first attempt, a thirty-six-yard field goal, an errant snap prevented him from even kicking the ball. On the next try, the snap was again poor, and he missed. The third snap was decent, and Del Toro split the uprights.

“It all has to be perfect or it gets messed up,” Del Toro said.

The line of scrimmage was moved back six yards, a forty-two-yard attempt from the right hashmark, a spot that Del Toro did not like. He had missed a field goal from that right hashmark in the playoffs the previous year, and he could not get the thought out of his head. Like a golfer with the yips, he was unable to put enough charge into the ball to reach the crossbar. He missed the first attempt short and to the right, just as he said he would. Del Toro, however, nailed the second attempt from forty-two yards.

“See, you can do it,” I told him afterward.

I met the father of a former player and two current tight ends, Nasir Ray and Justin Feggins. A former Clay-Chalkville running back, Terelle West, was on hand for practice. I covered West when he played for Clay-Chalkville from 2012 to 2014. He burst on the scene as a sophomore, breaking long touchdown runs in seemingly every game. He finished that season with more than nine hundred yards. As a junior, he ran for nearly 1,200 yards on just 130 attempts. During the Cougars’ run to an undefeated season and state championship in 2014, he tore his ACL in the playoffs, but not before he had amassed 1,400 rushing yards and nineteen touchdowns. Still, once the blue map was presented to players in Auburn University’s Jordan-Hare Stadium after a 35-31 classic against Saraland High School, West was front and center, lifting a blue map high for fans to see. He told me that this team, the 2025 Cougars, needed personality and leadership, traits that teams he played on had.

After practice, Floyd implored his players to hydrate well during the week leading up to the spring game at McAdory High School that Friday, four days away. It was going to be in the mid eighties at kickoff, and preventing cramps was going to be crucial. Covering their knees with their kneepads, he lamented, was key to preventing staph infections. Taking care of their bodies and knowing the difference between hurt and injured were also takeaways.

“If we ain’t got nobody to play, it ain’t no good,” Floyd said.

I sat on a long bench against the fieldhouse after practice. I listened as players talked with each other about the day and what was to come. Josh Ivy, a safety, said hey to me and asked what the title of my book was going to be. I told him that the spring, summer, and fall would have to play out, that the story would determine the title. West also remained to train current and former players. He apparently heard some discussions he didn’t care for and told the young guys to stop. They laughed and called him a chaperone, like he was the old guy. If they only knew how much older than West I was. Maybe they knew already.

“We all gonna get old one day,” one player said. “[West] is just old now.”

The discussion, which I did not hear most of, had something to do with gangsters and football players, about understanding perspectives of being from where they are from. West said he was trying to get them to understand the meaning of age and thinking about issues down the road instead of in the moment.

“When you get in your feelings, stuff don’t go right,” I remember him saying.

Not long after that discussion, the group was off to work on footwork and release point drills, and I left for the day. The long-awaited thunder approached, finally. It had held off all afternoon, but it finally arrived as the day was ending. The sky was a deep blue as I climbed the steep sidewalk to the parking lot. I quickly stopped at the old practice field above the stadium, just to look around.

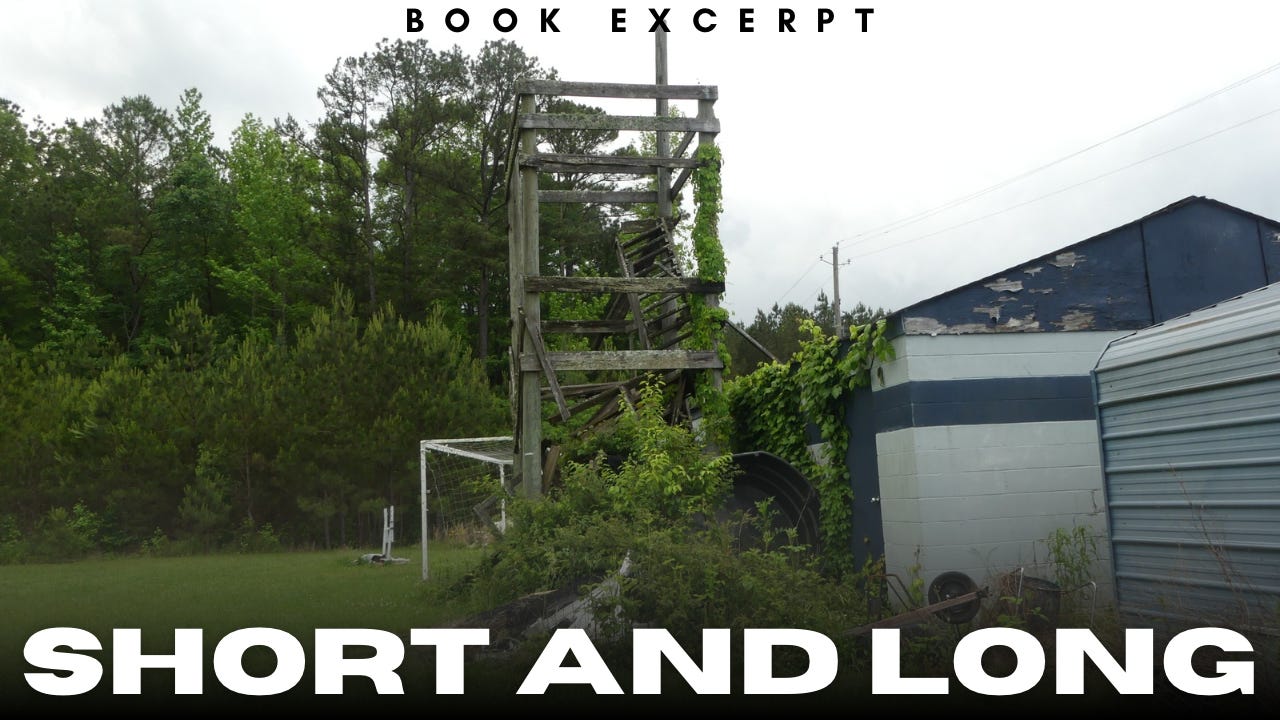

A walk-behind lawnmower rested at the edge of the woods, abandoned. Grass was thick, wet, and weedy. Trash – mostly paper plates and plastic cups – overflowed the cans near the top of the bleachers. Blue lockers, rusting at their hinges, sat behind a metal shed. A nearby coach’s tower, the kind that Paul “Bear” Bryant made famous at the University of Alabama, was overwhelmed by weeds and kudzu vines. Most of the wooden planks that made up the ladder had fallen away from the tower. A brick building, painted blue and gray, was open at its rollup door. I cautiously walked in. There was an old weed eater, lawnmower, hard hat, cooler, treadmill, and whiteboard with explicit phrases written in orange and red. A pile of old clothes lay in a corner, a red toolbox sat near a pile of yellow cords, and a binder of what I assume was a playbook was too dusty to make sense of.

Another rumble of thunder and an increasing mist let me know that it was time to leave. A storm was coming. As I exited the building, I noticed some sort of sign peeking out of the wood line. I could tell there was a cougar logo at the bottom, and the words “We promise,” “Cherished,” and “We will uphold” on the left side. The rest of the white sign was mostly destroyed, either by the elements or potentially fire. It was gray and black in the middle, with a gaping hole at what looked like its center. I searched out those key words later and found that they were part of Clay-Chalkville High School’s alma mater.

Clay-Chalkville High, we sing our praise to you

Silver and Blue we pledge our hearts be true

Here, in this valley with maple, oak, and pine

Stands proud our Alma Mater Clay-Chalkville High

These sacred halls render knowledge

Lend us the Cougar’s strength for tomorrow’s outstretched hand

We promise to treasure and keep for a lifetime cherished memories tender and strong

We will uphold her in everything we do

Clay-Chalkville High, forever we’ll be true